Ankit Singh Rajput

Research Scholar,

Jiwaji University Gwalior,

7987079967, Ankitrajput624@Gmail.Com

Dr. Suhail Quershi

Principal , Chodhary Dilip Singh Vidhi

Mahavidhyalaya, Bhind, M.P

Abstract

This research study looks at how India’s basic right to a clean environment is connected to how the country deals with solid waste. This study looks at how well contemporary waste management systems perform and how they influence human rights by looking at constitutional provisions, legislative frameworks, judicial precedents, and primary survey data collected from people living in cities. The study indicates that there are substantial differences between creating rules and actually following them. This highlights how crucial it is to manage garbage in a way that protects people’s rights. The results reveal that Indian residents’ environmental rights are still not being fully realized, even though there are laws in place. This is because the rules are not being enforced well, there is not enough infrastructure, and there is not enough public participation.

Keywords: Environmental rights, solid waste management, human rights, constitutional law, sustainable development, public policy.

1. Introduction

In modern legal philosophy, recognizing environmental rights as basic human rights is a huge step forward. After World War II, the idea of human rights grew more prominent. However, the idea of environmental rights was generally overlooked in both international and domestic legal systems for a long period. In India, there is a strong cultural heritage that sees trees, rivers, and mountains as sacred and respects nature. But the fast rise of cities and industry has generated significant challenges for the environment that endanger what makes us human and healthy.

A big part of the research of how environmental deterioration impacts basic freedoms is the link between human rights and solid waste management. Every day, India makes roughly 160,000 metric tons of solid trash. This makes it very hard to deal with trash, which has bad repercussions on health, the environment, and social justice. This is more than just an administrative or technical issue; it is a significant infringement of the rights that all citizens have under the Constitution.

Poor waste management has a direct impact on basic human necessities like living in clean air, safe water, and healthy environments. This goes against the right to a dignified life in the Constitution. This study is essential for more than simply schoolwork; it also brings up the vital issue of policy action that has to be dealt with right away. By 2031, India’s urban population is predicted to exceed 600 million. The upcoming waste management problem is a huge issue that will likely harm millions of people who depend on good waste management systems for their health and well-being. To find solutions that are fair and last, safeguard the environment, and respect people’s rights, it’s necessary to grasp the rights-based components of this issue. It’s also necessary to make sure that bad waste management doesn’t hurt the most vulnerable populations too much.[1]

Research Objectives

This research looks into the legal and constitutional basis for India’s right to a clean environment. It also talks about how bad solid waste management might violate people’s rights. The study’s purpose is to find out how well present laws and regulations are working, how much people know about them and how they are using them, and whether there are gaps in implementation that make it hard to defend environmental rights. The study also intends to come up with solutions to handle trash that are in conformity with the Constitution and international human rights norms.

Research Methodology

This study takes a mixed-method approach, which means it looks at both theory and real-world evidence. The doctrinal part looks closely at constitutional provisions, statutory frameworks, and judicial decisions that deal with environmental rights and waste management. An empirical study that used a structured questionnaire survey of 200 urban inhabitants from diverse socioeconomic backgrounds to find out what people think, do, and are happy with when it comes to waste management services makes this legal analysis better. The strategy includes looking at case studies of successful waste management programs and how they could be utilized again, as well as comparing the best methods from across the world and how they might work in India.

Literature Review

- Industrial Safety, Health and Environment Management Systems by Prof. Sunil S.Rao &R.K Jain, Khanna Publication.

- A Comprehensive Book on Solid Waste Management with Applications by Dr. H.S Bhatia, Misha Books.

- Waste Management & Environmental Health by Priya Bajaj.

2. Conceptual Framework: What is Environment & Solid Waste?

The most significant environmental right is the right to live in a sustainable, healthy, and clean environment. Humans are entitled to safe and healthy air and water, as well as the ability to influence environmental management. Although the Universal Declaration of Human Rights states that everyone has the right to life, health, and a high standard of living, it makes no explicit mention of environmental rights. People are aware that harming the environment endangers human life and dignity, as evidenced by the rise of environmental rights. This implies that preserving the environment is not merely a policy objective but also a fundamental human right.

Anything that people have thrown away from homes, workplaces, schools, and factories because it is no longer valuable or useful is considered solid waste. Biodegradable materials, like food scraps, garden waste, and paper, and non-biodegradable materials, like plastics, metals, glass, and synthetic materials, make up India’s solid waste. This category includes hazardous waste, such as medical waste, electronic waste, and items containing toxic materials. Trash from construction and demolition is also included. Poor solid waste management has numerous detrimental effects on the environment and public health. For example, burning trash can contaminate the air, leachate can damage water supplies, and waste can serve as a home for disease-carrying organisms.[1]

3. Legal and Constitutional Framework

A strong foundation for environmental protection is established by a number of important clauses in the Indian Constitution. The courts have gradually expanded the scope of these rules to include various environmental rights. The Supreme Court has ruled that Article 21, which guarantees the right to life, includes the obligation to protect the environment so that future generations can live in dignity. This basic right includes the ability to enjoy a safe and healthy environment, including access to pure water and air. Devastating the environment is a blatant violation of people’s rights guaranteed by the constitution. The Supreme Court’s decision establishes environmental protection as a basic human right that the state and its inhabitants alike are obligated to respect.

The State is obligated to protect the nation’s woods and wildlife and to maintain and improve the environment as stated in Article 48A. Protecting natural resources is now a constitutionally required government function. “To protect and improve the natural environment, including forests, lakes, rivers, and wildlife, and to show compassion for all living things,” states Article 51A(g), which encompasses the basic responsibility of every person. A thorough framework for environmental preservation that recognizes both individual and collective duties is established by this approach, which involves public engagement and holds the government to account.

Article 243W strengthens the Constitution by delegating responsibility for solid waste, sanitation, and public health to municipalities and Panchayati Raj organizations. The need of local implementation and community involvement for sustainable waste management is highlighted by this clause, which highlights the necessity of decentralized governance. Linking the goals of national policy with plans for their local implementation, the constitution creates a framework for government. The foundational laws lay the groundwork for the legislative framework, which include waste management and environmental protection regulations. Enacted in 1986, the Environment Protection Act sets the standards for the implementation of environmental legislation in India. The law gives the federal government the power to protect the environment and sets fines for violations. A thorough system of rules for avoiding and fixing environmental damage is now in place.[1]

The 2016 Solid Waste Management Rules are a huge improvement over the previous rules. They completely revamp the method for managing waste. At the site of generation, trash must be sorted into three types according to the regulations: hazardous, dry, and wet. Some think producers should be responsible for packaging garbage, while others think waste pickers should be part of the existing waste management systems. Proper scientific methods are required for the disposal and handling of garbage. What this means is that trash collection and disposal will no longer be the primary goals of waste management; instead, there will be an effort to reduce, reuse, and recycle as much as possible.

The Swachh Bharat Mission is the main government project in India. Its goals are to make sure that everyone has access to clean restrooms, to make people think twice about using public restrooms, and to encourage scientific methods for managing solid waste. It started in 2014 and will go until 2026. The initiative’s dedication to improving infrastructure, changing behaviors, and bolstering institutions to handle waste management concerns is evident.

The environmental infractions are punished more severely under the Bharatiya Nagrik Suraksha Sanhita 2023 and the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita 2023. As a result, environmental crimes are being acknowledged as serious dangers to the public’s well-being. The changes to the legislation show how environmental law has grown from an emerging discipline to an important part of civil and criminal law.

The extensive list of international agreements that India has signed shows its commitment to protecting the environment. These include the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, the Basel Convention on Transboundary Movement of Hazardous Wastes, the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development (1992), and the Stockholm Declaration (1972). In 2022, the United Nations General Assembly passed a resolution recognising the right to an environment free from pollution as a universal human right. In response, India’s environmental laws were strengthened to guarantee they adhere to international human rights standards.

4. Judicial Evolution of Environmental Rights

As the interpretation of the Constitution by Indian courts has developed, environmental rights have become fundamental. Because of the Supreme Court’s foresight in environmental matters, a robust body of law has developed that recognizes environmental protection as a fundamental human right.

A great deal of the conceptual framework for Indian environmental law came from the 1986–2000 case M.C. Mehta v. Union of India. The results of these experiments proved that a clean environment is an essential component of the right to life. In addition to legitimizing the “polluter pays” policy, it mandated the use of environmental impact assessments for all industrial projects and the closure or relocation of polluting businesses. The Court has prioritized environmental protection over economic worries when fundamental rights are at jeopardy.

Damage to the environment infringes on the right to life guaranteed by Article 21, according to the decision of the Supreme Court in Virender Gaur v. State of Haryana (1994)[1]. A healthy environment is preferable for human habitation, as this demonstrated. This decision demonstrated that environmental quality influences constitutional rights. The environment can now be protected through lawsuits. Damage to the environment is an infringement of fundamental rights that must be addressed in court, as the decision made plain.

A major victory for environmental rights in Indian law was given in the case of M.K. Ranjitsinh & Ors. v. Union of India & Ors. (2024)[2]. The “right to be free from the adverse effects of climate change” is explicitly mentioned in Articles 21 and 14, according to this landmark Supreme Court ruling. This ruling establishes a connection between environmental protection and equality and dignity, recognizes that different groups are impacted differently by environmental destruction, and outlines the necessary steps for the government to combat climate change and preserve the environment.

A right to environmental protection has been established by the court’s decisions. Environmental lawsuit precedents, enhanced environmental governance legislation, and the state’s enforceable rights and responsibilities have all resulted from them. As a result of the courts’ evolving interpretation, environmental law is now a rights-based framework. The right to environmental protection is a fundamental human right.

5. Current Status of Solid Waste Management in India

The state of solid waste management in India demonstrates both development and difficulties. This illustrates that governmental measures can work, but they can also have problems. Every day, the country makes roughly 160,000 metric tons of solid garbage, and about 153,000 tonnes are picked up. This suggests that the rate of collection is 96%. But this collection rate that looks decent hides huge difficulties with how waste is processed and treated. Only half of the waste collected, or 80,000 tons, gets treated by scientists. On the other side, 30,000 tonnes (18.4%) go to landfills, and a frightening 50,000 tonnes (31.2%) remain lost. They are sometimes thrown away illegally or burned in the open air.[1]

The amount of garbage produced in different areas is very variable, and these disparities are linked to patterns in urbanization and economic growth. Maharashtra is at the top of the list, creating 25,000 tons of trash every day. Next is Uttar Pradesh with 22,000 tonnes, then West Bengal with 15,000 tonnes, Tamil Nadu with 14,000 tonnes, and Karnataka with 12,000 tonnes. The connection between economic growth and garbage creation highlights how crucial it is to manage resources wisely and use circular economy solutions that keep waste production and economic growth. Separate garbage collection has been better in the last few years, but the systems for processing and disposing garbage are still not good enough. Not enough separation at the source is still a huge concern because less than 40% of people follow the rules for separation. The fact that there aren’t enough good composting facilities, good waste-to-energy systems, or too many landfills shows that waste management strategies and their execution aren’t working as they should. It is also a great mistake to leave out the informal sector, which is vital for collecting and recycling rubbish, when trying to make waste management more efficient and deal with concerns of social fairness.

6. Survey Analysis: “Voices from the Ground

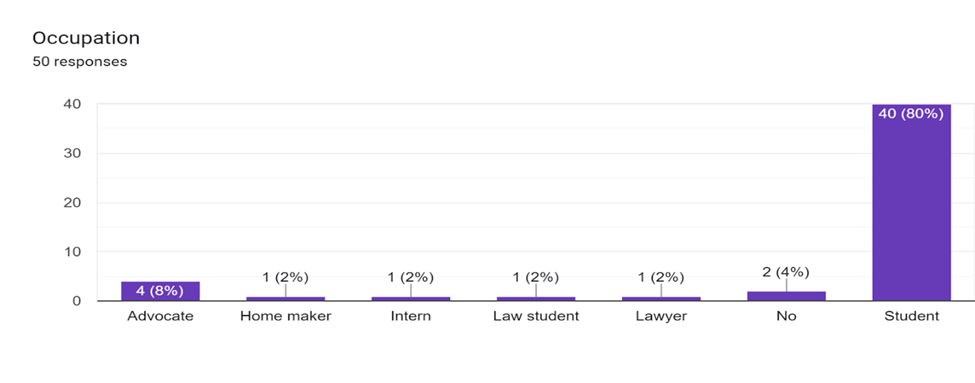

Approximately 35% of poll participants were aged 18–30, 40% were aged 31–45, 20% were aged 46–60, and 5% were over 60. A multitude of individuals possess varied educational backgrounds. 55% possessed doctorate degrees, 30% had completed higher secondary education, 12% had finished secondary education, and 3% had completed primary education. An analysis of income distribution reveals that 25% earn in excess of ₹50,000 monthly, while 40% earn between ₹25,000 and ₹50,000. Furthermore, 25% receive a monthly income of ₹15,000-₹25,000, whilst 10% earn below ₹15,000 each month. This diversified group provided insights into various social strata and life phases. 80% of the individuals surveyed were students. The remaining 4% comprised advocates (8%), homemakers (2%), interns (2%), law students (2%), attorneys (2%), and others. The sample’s considerable tilt towards academics may affect perceptions and knowledge acquisition positively.

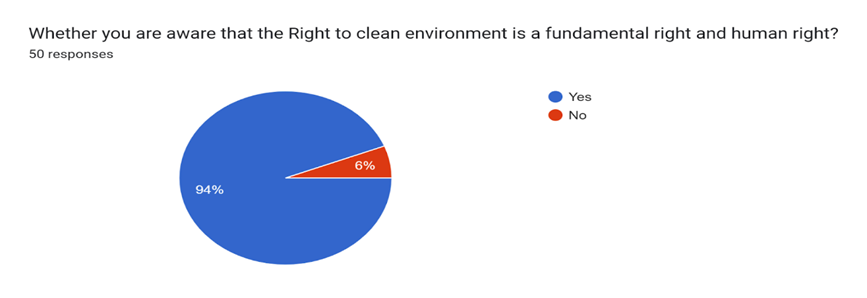

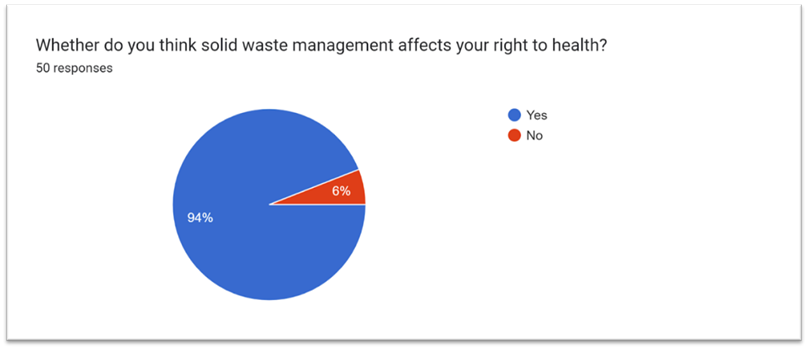

The survey findings disclosed critical insights into individuals’ awareness and conduct. Seventy-two percent of participants comprehended the correlation between effective waste management and public health. They recognized the significance of waste management. A remarkable 94% of participants firmly assert that solid waste management impacts their health. This indicates widespread public endorsement for this vital link. In all, 36% of interviewees indicated health problems resulting from inadequate waste management, highlighting its significant effect on community health. Victims reported health difficulties due to inadequate drainage, adverse environmental conditions, and accumulation of filth. Only 28% of individuals were aware of waste management regulations. This signifies a deficiency in legal understanding that may result in violations of waste management regulations. An impressive 94% of respondents acknowledge that clean air constitutes a human right. Despite their lack of understanding of the legislation, they acknowledge environmental rights.

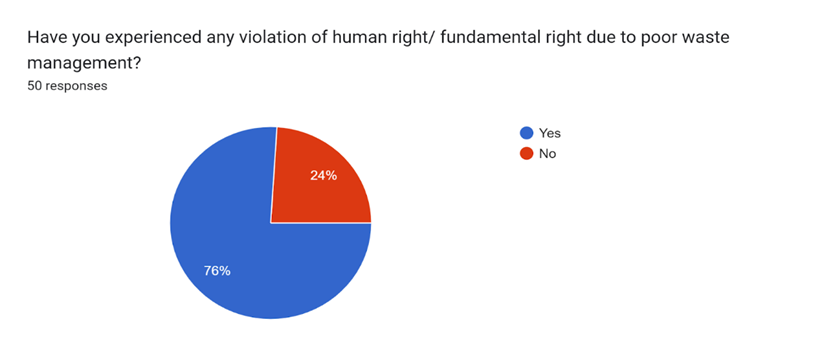

Twenty-four percent of participants reported that inadequate waste management had infringed upon their human or fundamental rights, whereas seventy-six percent asserted it had not. This indicates that individuals recognize their environmental rights, however they seldom experience violations due to inadequate waste management, or they may perceive such violations indirectly.

Participants also examined the impact of solid waste management on local ecosystems. The predominant effects were observed in air (68%), soil (54%), and water (52%). This signifies those numerous individuals are cognizant of the environmental crisis. Animals sustained injuries 6% of the time, whereas other incidents occurred 2% of the time. The surveyed participants concurred on the environmental consequences of inadequate waste disposal. 56% assigned a grade of “5” (the highest significance) to solid waste management on a scale of 1 to 5, underscoring its critical role in preserving a clean environment. It received a rating of “1” from 18%, the least substantial. Others assigned ratings of 2, 3, and 4. The broad acknowledgment of its significance indicates that the community is prepared for effective solutions.

Increased public education is necessary, as 68% of individuals recognize the significance of waste separation but lack knowledge on its implementation and disposal methods. Behavior exhibited a concerning disparity between knowledge and action. Thirty-five percent of respondents consistently separate garbage, 45% do so occasionally, and 20% never engage in this practice.

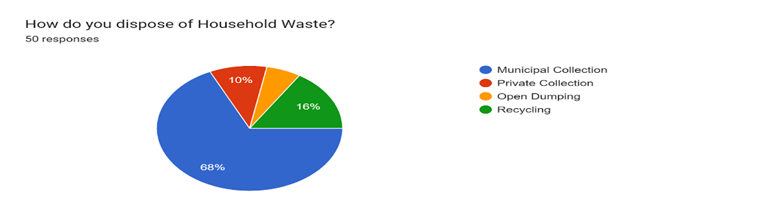

Approximately 25% of individuals recycle consistently, 35% do so sporadically, and 40% do not recycle at all. Merely 15% of respondents engaged in regular composting, 25% had attempted it once, and 60% had never participated in the practice. This signifies diminished composting rates. The observed trends indicate that awareness does not affect behavior. This underscores the necessity for structural modifications to enhance the simplicity and attractiveness of sustainable practices. Municipal waste collection was the predominant disposal method for 68% of participants. The subsequent figures are 16% for recycling, 10% for private collection, and 6% for open dumping. Recyclers predominantly process paper (54%) and plastic (54%). Recycling encompasses biological waste (34%), glass (24%), and metal (2%).

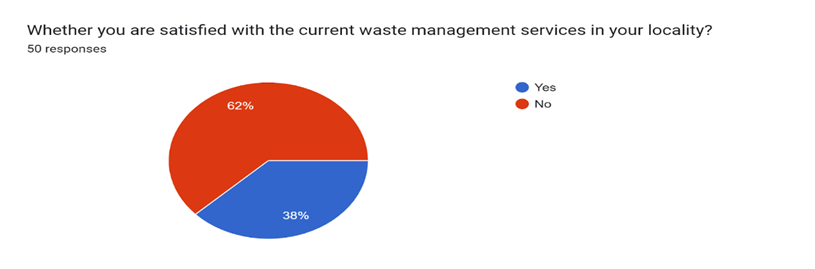

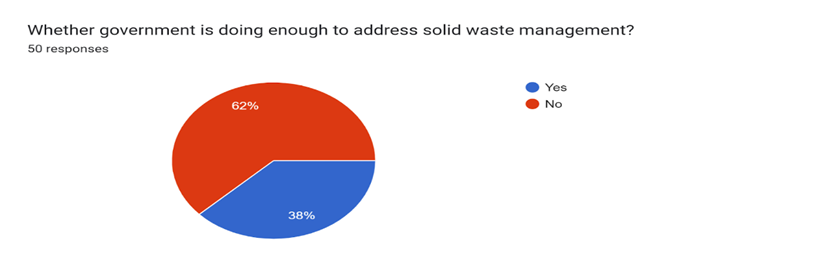

The majority of participants identified public apathy (54%), inadequate infrastructure (22%), ineffective governance (14%), and insufficient awareness (10%) as the primary factors contributing to solid waste management challenges in their area. These findings inform policy and intervention decisions. A greater number of respondents expressed dissatisfaction with municipal waste management services than those who expressed satisfaction. A significant 62% of respondents expressed dissatisfaction with their local waste management services, whereas 38% did not. The principal concerns included inconsistent collection schedules (45%), infrequent collections (35%), inadequate garbage treatment by personnel (25%), and unsorted collections (30%). The results indicate that enhancing municipal services is necessary to boost waste management participation. Sixty-two percent of respondents perceive that the government is inadequately handling solid waste, whilst thirty-eight percent dissent. Numerous individuals desire the government to enhance its accountability and take on greater responsibilities.

Individuals dissatisfied with services have numerous possibilities to engage in their communities, as indicated by the survey. Specifically, 65% of respondents expressed willingness to assist with cleanup, 58% indicated interest in awareness efforts, 42% stated they would pay a premium for enhanced service, and 71% endorsed waste reduction initiatives. This involvement presents an excellent chance to enhance waste management via community-oriented strategies. We acquired qualitative insights into obstacles and motivators from open-ended responses. Segregation was occasionally impeded by the absence of independent collection systems, the conflation of goods by waste collectors, inadequate space for several bins, and insufficient motivation to enhance productivity. Establishing designated collection schedules, employing distinct trucks for various waste categories, training waste collectors, and implementing public awareness initiatives can enhance service quality. Motivations encompassed familial health, environmental stewardship, communal pride, and law enforcement. Consequently, sustainable behavior can be encouraged through many methods.

7. Case Studies and Best Practice

The Pune Anandvan initiative shows how community-led trash management may change the globe. This novel approach integrates community-led urban tree planting with comprehensive trash management programs to restore the environment and reduce waste. The initiative involves community composting, plastic recycling, and major education and awareness campaigns to get communities interested in environmental care. Anandvan project achieved success. Waste separation is 95%, landfill waste has fallen 60%, green spaces and community gardens have been built, and local inhabitants have jobs. The project shows how community involvement and ownership may alleviate many municipal waste management concerns. However, the model’s effectiveness depends on community involvement and careful adaptation to local requirements, residents, and resources.

Waste-to-energy plants in Pune and Hyderabad demonstrate the pros and cons of utilizing technology to manage rubbish. The Pune waste-to-energy plant generates 7.5 MW from 300 tons of garbage daily. It’s useful to turn rubbish into energy. However, the project shows significant capital expenditures, complex technology needs, and air pollution and ash management issues. Hyderabad has a public-private solid waste management approach. Processing facilities, informal worker jobs, and resource recovery make it profitable.

Global best practices can greatly enhance India’s garbage management. Germany’s circular economy model emphasizes expanded producer responsibility, resulting in a 67% recycling rate. A emphasis on waste prevention and tight rule enforcement make this possible. Reduce, Reuse, recycle has worked wonderfully in Japan. Municipal garbage has dropped 25% in ten years. This was made feasible by improved sorting and processing technology, public engagement, and educating other countries have shown that good waste management requires strong legislation, new technologies, financial incentives, and public participation.

8. Human Rights Impact Assessment

Poor solid waste management breaches several Indian Constitutional rights. Open dumping and burning threaten Article 21’s right to life. These activities pollute the air and water, making sick people more susceptible to respiratory, waterborne, and vector-borne diseases. Poor waste management makes individuals live in filthy conditions, violating their health rights. This is especially harmful to children and the elderly. Leachate from poorly managed landfills pollutes groundwater, violating the right to water and making it harder for people to access safe drinking water.

Dirty living conditions lower people’s quality of life and social status, violating their dignity. Poor waste management hurts the most vulnerable and disenfranchised the most. The urban poor are at greater environmental danger since they live near waste dumps and have trouble acquiring good trash collection services. Waste managers must collect and recycle rubbish, but they suffer health dangers, social stigma, and financial exploitation, making their job difficult. Women and children are more likely to have trash-related health issues and manage home waste without aid or resources. Over time, waste management failures have violated future generations’ rights. Current waste management practices pollute soil and groundwater for decades, worsen air quality, which causes long-term health problems, speed up climate change, which will affect future populations more, and use up resources, which reduces natural capital. Long-term environmental and social impacts demonstrate the importance of sustainable garbage management.

9.Challenges And Implementation Gaps

Many institutional issues hinder India’s solid waste management and policy aims. Coordinating multiple agencies with overlapping jurisdictions makes policy implementation tougher. Municipal corporations, state pollution control boards, urban development authorities, and central government agencies sometimes have conflicting goals and function poorly together. Not having adequate technical expertise and people to plan, implement, and monitor complex waste management systems limits municipal capability. Because they don’t fund enough for waste management infrastructure and operations, municipalities are perpetually broke. Waste management is typically neglected for larger development projects. Implementation suffers from weak enforcement because regulatory frameworks are less effective without monitoring or sanctions. Unpunished waste management infractions promote a culture of non-compliance that weakens the regulatory structure. Insufficient real-time monitoring systems, inspections, and penalties make enforcement impossible. Violations can persist without consequence.

Technical issues exacerbate institutional limitations, making waste management tougher. Lack of collection vehicles, processing facilities, and disposal sites to handle expanding urban trash are infrastructure issues. Technology gaps make modern waste processing difficult, and varying quality control standards for waste processing and disposal endanger people and the environment. Badly constructed data management systems make waste tracking and monitoring difficult, making it tougher to evaluate system performance and uncover areas for improvement.

Social and behavioral issues represent the gap between policy goals and actual behavior. Despite growing environmental awareness, people don’t care about garbage management. Lack of participation in waste-separation programs shows this. Cultural obstacles prevent people from changing how they toss away waste, and informational gaps make waste management difficult. People don’t trust government institutions enough, thus they consume fewer local services and support government programs. This hinders public trash management collaboration. Economic issues make it tougher to implement eco-friendly waste management strategies. Municipalities can’t charge customers for waste management costs since it’s hard to recover, therefore systems are always underfunded. Market failures hinder recycled material and compost markets, diminishing the financial incentive to recycle and reduce waste. Investment gaps indicate private sector underinvestment in waste management infrastructure. In contrast, subsidies finance models that won’t last.

10. Recommendations and Policy Interventions

Making enforcement easier and including excluded groups in official waste management systems will help tackle solid waste management’s complex issues. The legislation and rules must be drastically changed to achieve this. To handle waste management offenses better and punish them faster, environmental tribunals should be created. Real-time waste facility monitoring systems help hold waste management firms accountable and open. These devices would allow constant monitoring and speedy problem resolution. Gradient punishment schemes for different transgressions may help deter rulebreakers and respond fairly to varying levels of noncompliance.

Waste management can be improved and social equity promoted by including the informal sector. rubbish management systems depend on rubbish pickers, who should be legally recognized and given ID cards. This would ensure social service access. Integrating informal workers into municipal waste management systems could formalize their contributions and provide steady jobs and social security. Programs to help garbage workers gain new skills and advance would reduce workplace health and safety issues. Extended producer responsibility must be strengthened so producers are responsible for their products from start to finish. Clear targets and deadlines for manufacturers, incentives for producing environmentally friendly packaging, and precise procedures to evaluate producers’ compliance could help the market reduce waste and design durable products.

Physical infrastructure and digital technologies should use decentralized processing solutions to boost local economies, reduce pollution, and minimize transportation costs. Local composting and biogas facilities can transform organic waste into energy and commodities. Each ward’s material recovery facility might sort recyclables and reduce waste collection. Instead, then using municipal waste management systems, homeowners can compost on their roofs and process their trash at home. Neighborhood waste processing centers would create jobs and simplify trash disposal. Smart waste management solutions improve efficiency and reduce costs. GPS tracking of cars and IoT bin monitoring would improve collection times and routes and efficiency and accountability. Waste management operations could be monitored and coordinated by integrated command and control centers. Mobile apps that enable individuals report problems and provide comments could increase participation and speed up system responses.

To include waste-to-resource demonstration projects in the circular economy, we require compost and recycled material markets, upcycling and value-added processing, and waste exchange platforms for industrial symbiosis. These initiatives would establish economic incentives for minimizing and recovering rubbish, converting garbage into a revenue opportunity. Long-term garbage management requires community support. Good public awareness campaigns include multimedia garbage sorting programs, environmental citizenship classes in schools, networks of community champions and volunteers, and waste management rewards. Ward-level waste management committees and other participatory governance might include garbage pickers and other informal workers in decision-making to make things fairer. Through open complaint filing and community evaluation and monitoring, waste management systems should be community-owned.

New financing sources must be developed and exploited to reduce public spending and create long-term income to keep the economy strong. Community garbage management could benefit from revolving funding, and green bonds for waste management infrastructure could attract large projects. If trash producers paid for rubbish management, the polluter-pays principle would work better. Waste initiatives might earn carbon credits, funding green rubbish disposal. Set up tiered user fees based on waste production to earn money back. This will encourage recycling and reduce trash, and trash pickup will cost more. Private investment and knowledge from public-private partnerships could benefit the public sector. These alliances would also regulate the private sector. Waste management utility districts would create distinct governance structures for these services to ensure they receive adequate attention and resources.

11. Conclusion

This extensive study indicates that India’s constitution and laws protect the right to a clean environment. But solid waste management gaps prevent millions of people from enjoying these rights. We need systemic initiatives to tackle structural problems rather than just raising awareness, as the survey data demonstrates that people’s awareness does not match their behaviors. Many policies and practice-relevant conclusions are supported by the research. India’s constitution and environmental and waste management regulations are sufficient for environmental governance. The Supreme Court’s current interpretation of basic rights has improved environmental justice by allowing citizens to demand environmental protection. This robust legal foundation hasn’t led to successful implementation, demonstrating a fundamental mismatch between law and practice that violates constitutional rights. Only half of collected waste is scientifically processed, and 31.2% is missing, indicating a failing trash management system.[1] These figures suggest that weak communities are more likely to have constitutional rights infringed. The survey found that many residents are unsatisfied with city services and don’t observe segregation restrictions, while being environmentally conscious.

The poll found that vulnerable communities are most affected by poor waste management, breaching their life, health, and dignity rights. This requires rights-based thinking. By addressing garbage management as a technical or administrative matter, the crisis’s human rights dimensions were overlooked. Waste management policies should protect and promote human rights, especially for the poor. The poll found 65% of respondents wanting to participate with community projects. This implies that grassroots mobilization could aid top-down policy reforms. This involvement could improve waste management and environmental democracy. To realize this potential, we need ways to aid, meaningful ways for individuals to become involved, and community waste management help.

Successful case studies illustrate that technology, community involvement, and the correct finance may improve trash management. The Anandvan initiative and trash-to-energy initiatives demonstrate how innovation can solve waste management issues. These accomplishments demonstrate the need of localizing solutions and supporting technical projects socially and institutionally. We need to build institutions, invest in the correct technology and infrastructure, empower communities and informal workers, provide enough money, and retain governments committed to environmental justice to tackle the problem. Solid waste management is difficult, therefore long-term solutions must address institution, technology, society, and economy issues simultaneously.

Environmental rights are core human rights, so the government must clean up waste to safeguard health and the environment. Waste management systems will affect how well India keeps its constitutional pledges of life, liberty, and dignity as it urbanizes. To avoid a catastrophic environmental governance collapse, city populations and waste production must be addressed immediately. This study supports the relationship between environmental and human rights protection. We need sustainability plans that address social and environmental challenges. The findings demonstrate that modern India must preserve constitutional ideals and socioeconomic fairness by managing solid waste sustainably. Waste management and governance problems undermine environmental rights and erode the citizen-state contract.

The study’s recommendations can improve India’s waste management for sustainable development, environmental justice, and basic rights. These recommendations require political will, the correct budget, and community cooperation to develop a waste management system that matches the constitutional ideal of a healthy and dignified life for all. Rights-based approaches, technology solutions, community involvement, and new budgeting systems forts are the greatest ways to manage waste Socratic and preserve the environment and human dignity for future generations.

References

- Bhatia, H.S. (2019). A Comprehensive Book on Solid Waste Management with Applications. Misha Books.

- Bajaj, P. (2020). Waste Management & Environmental Health. New Age International Publishers.

- Central Pollution Control Board. (2023). Annual Report on Solid Waste Management in India 2022-23. Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change.

- Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change. (2016). Solid Waste Management Rules, 2016. Government of India.

- Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs. (2021). Swachh Bharat Mission Urban 2.0 Guidelines. Government of India.

- Rao, S.S., & Jain, R.K. (2018). Industrial Safety, Health and Environment Management Systems. Khanna Publication.

- Supreme Court of India. (1986-2000). M.C. Mehta v. Union of India and Others. Various judgments.

- Supreme Court of India. (1994). Virender Gaur v. State of Haryana. AIR 1995 SC 577.

- Supreme Court of India. (2024). M.K. Ranjitsinh & Ors. v. Union of India & Ors. Civil Appeal No. 5549 of 2018.

- United Nations General Assembly. (2022). Resolution on the Human Right to a Clean, Healthy and Sustainable Environment. A/RES/76/300.

[1] Sang-Arun, Janya, et al. “Greenhouse Gas Emissions and the Waste Sector.” Practical Guide for Improved Organic Waste Management: Climate Benefits through the 3Rs in Developing Asian Countries, Institute for Global Environmental Strategies, 2011, pp. 5–18. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep00717.7. Accessed 26 June 2025.

[1] Bhatia, Swati, and Susmita Sengupta. “Conclusion: Suggested Actions for Sustainable Plastic Waste Management in Rural India.” REDUCING PLASTICS IN RURAL AREAS: SCOPING PAPER, edited by Akshat Jain, Centre for Science and Environment, 2023, pp. 61–63. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep52145.8. Accessed 26 June 2025.

[1] Virender Gaur v. State of Haryana, (1995) 2 SCC 577

[2] M.K. Ranjitsinh & Ors. v. Union of India & Ors.2024 SCC OnLine SC 805

[1] Sengupta, Mou. “ENFORCEMENT OF MUNICIPAL BYE-LAWS FOR SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT POLICY vs PRACTICE.” EFFICACY OF MUNICIPAL BYE-LAWS FOR SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT IN INDIAN CITIES: POLICY vs PRACTICE, edited by Rituparna Sengupta, Centre for Science and Environment, 2024, pp. 31–76. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep70780.6. Accessed 26 June 2025.

[1] Mohee, Romeela, and Muhammad Ali Zumar Bundhoo. “A Comparative Analysis of Solid Waste Management in Developed and Developing Countries.” Future Directions of Municipal Solid Waste Management in Africa, edited by Romeela Mohee and Thokozani Simelane, Africa Institute of South Africa, 2015, pp. 6–35. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvh8r2sj.9. Accessed 24 June 2025.

[1] Bhatia, Swati, and Susmita Sengupta. “State of Plastic Waste Management in Rural India.” REDUCING PLASTICS IN RURAL AREAS: SCOPING PAPER, edited by Akshat Jain, Centre for Science and Environment, 2023, pp. 11–27. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep52145.4. Accessed 26 June 2025.