Mahima Gupta,

Clinical Psychologist,

school of behavioural sciences and forensic investigation,

Rashtriya Raksha university, Gujarat, India.

Dr. Gaurav Kumar Rai,

Scientific officer, Forensic Science Laboratory,

Lucknow-226006,Uttar Pradesh, India

Abstract:

Background: Exposure to environmental radiation, particularly electromagnetic and earth radiation, has emerged as a significant public health concern due to the potential physical and psychological impacts. Communities in radiation-affected areas frequently face chronic uncertainty, health-related worries, and protracted environmental stress, all of which can have a negative impact on numerous aspects of psychological functioning. However, empirical research on multidimensional stress indicators among such individuals in rural India is scarce. The current study aims to examine and evaluate stress indicators among people residing in radiation-affected and non-affected areas of Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh. Method: A comparative cross-sectional research design was adopted. The sample comprised 60 adult participants, with 30 from Pure village (an electromagnetic and earth radiation-affected area) and 30 from Gangapur village (a non-affected area), located approximately 20 km apart. Stress was assessed using the Stress Indicator Questionnaire, which measures five dimensions: physical, sleep, behavioural, emotional, and personal indicators. Data were analysed using descriptive statistics (Mean and Standard Deviation) and inferential statistics (independent sample t-test).Outcome: Findings revealed that participants from the radiation-affected village exhibited significantly higher levels of stress on physical, sleep, behavioural, and emotional indicators compared to the non-affected group. In contrast, differences in personal stress indicators between the two groups were minimal and statistically non-significant. These results indicate that chronic exposure to environmental radiation is associated with elevated stress responses across multiple domains of functioning.Conclusion: The study concludes that residence in radiation-affected areas is associated with significantly higher multidimensional stress, particularly in physical, sleep-related, behavioural, and emotional domains. The relative similarity observed in personal indicators may reflect adaptive coping mechanisms or resilience within affected communities. These findings highlight the need for targeted psychosocial interventions and mental health support for populations living in environmentally hazardous regions, alongside continued monitoring of environmental risks.

Keywords: Radiation exposure; Stress indicators; Environmental stress; Electromagnetic radiation; Rural population; Varanasi

Introduction: Stress has long been recognized as one of the most pervasive psychological phenomena, influencing nearly every aspect of human functioning. It is commonly defined as a state of physiological and psychological arousal that arises when environmental demands exceed an individual’s coping resources (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). The General Adaptation Syndrome, which describes the body’s reaction to prolonged demands in three stages—alarm, resistance, and exhaustion—was first proposed by Hans Selye in 1956. This biological perspective laid the groundwork for later psychological models of stress. Over time, stress research has diversified into a multidimensional construct encompassing physical, emotional, behavioural, cognitive, and social facets (Cohen, Kessler, & Gordon, 1995).

While short-term stress may be adaptive and enhance performance, chronic stress has been consistently linked to adverse mental and physical health outcomes, including anxiety, depression, cardiovascular disease, immune dysfunction, and sleep disturbances (McEwen, 1998; Schneiderman, Ironson, & Siegel, 2005).

Environmental adversity represents one of the most potent and persistent sources of chronic stress. Individuals exposed to hazardous environments—such as natural disasters, industrial accidents, or toxic pollutants—demonstrate significantly higher stress levels than those residing in non-hazardous settings (Norris et al., 2002). Among environmental hazards, radiation exposure is particularly distressing due to its invisible, uncontrollable, and uncertain nature (Slovic, 1987). The psychological consequences of radiation exposure often extend far beyond the period of physical danger.

Evidence from major nuclear disasters underscores the long-term psychological toll of radiation exposure. Studies following the Chernobyl nuclear accident (1986) documented elevated levels of anxiety, somatic complaints, depression, and post-traumatic stress symptoms among affected populations, even decades after the incident (Bromet et al., 2011; Havenaar et al., 1997). Similarly, research conducted after the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster (2011)revealed persistent psychological distress, sleep disturbances, and fear of genetic and intergenerational health effects among residents, including those who were not directly exposed to radiation (World Health Organization [WHO], 2013; Shigemura et al., 2012).

Importantly, the psychological impact of radiation exposure is not confined to physical health outcomes alone. Bromet and colleagues (2011) emphasized that psychosocial stress, stigma, and uncertainty often exert a greater long-term burden than radiation-induced illness itself. Survivors of Chernobyl reported experiences of social exclusion, discrimination, and internalized stigma, which intensified stress and undermined overall quality of life (Havenaar & Rumyantzeva, 2013). Similar patterns have been observed in communities exposed to industrial pollution and toxic waste, where perceived risk and lack of trust in authorities amplify emotional distress, regardless of actual exposure levels (Edelstein, 2004).

In the Indian context, awareness of the psychological consequences of environmental disasters has emerged gradually. The Bhopal gas tragedy of 1984 remains one of the most catastrophic industrial accidents worldwide. Long-term studies have documented high prevalence rates of psychiatric morbidity, including generalized anxiety disorder, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and somatoform disorders among survivors (Varma & Varma, 2005; Patel et al., 1998). Decades after the disaster, affected individuals continued to report sleep problems, chronic fatigue, somatic complaints, and feelings of helplessness, reflecting sustained exposure to chronic stress (Mathur, 2006). These psychological outcomes were further exacerbated by poverty, inadequate healthcare access, and prolonged uncertainty regarding future health consequences.

Radiation exposure reported in rural areas of Varanasi district, Uttar Pradesh, presents a contemporary yet under-researched context of environmental adversity. Reports of congenital anomalies, chronic illness, and multiple physical disabilities within families have contributed to widespread fear, uncertainty, and financial strain. For caregivers and affected individuals alike, daily life is marked by ongoing stress related to health concerns, caregiving responsibilities, and economic hardship. Despite biomedical documentation of radiation-related health issues, systematic research examining psychological stress across multiple dimensions in these communities remains limited, representing a significant gap in the literature.

Understanding stress as a multidimensional phenomenon is particularly relevant in such settings. Physical indicators of stress include fatigue, headaches, musculoskeletal pain, and gastrointestinal disturbances, often linked to prolonged physiological arousal (McEwen & Stellar, 1993). Sleep indicators encompass difficulties initiating or maintaining sleep, non-restorative sleep, and insomnia, which are strongly associated with both emotional distress and physical illness (Morin et al., 2006). Behavioural indicators involve irritability, aggression, withdrawal, reduced productivity, and maladaptive coping strategies. Emotional indicators reflect heightened anxiety, fear, sadness, frustration, and depressive symptoms. Personal indicators relate to perceived control, self-efficacy, and coping capacity, which influence how individuals interpret and respond to stressors (Bandura, 1997).

A substantial body of research indicates that populations exposed to chronic environmental hazards exhibit significantly elevated stress across these domains. Survivors of natural disasters, such as floods, earthquakes, and tsunamis, report persistent sleep disturbances, psychosomatic symptoms, and emotional distress long after the event (Norris et al., 2002; Galea et al., 2005). For instance, studies following the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami found enduring insomnia, somatic complaints, and feelings of insecurity among survivors several years post-disaster (Silove et al., 2007). Comparable findings have been reported in industrial and radiation-related disasters, where uncertainty and invisibility of the hazard intensify psychological strain (Slovic, 2010).

Cultural and social resources play a crucial moderating role in stress experiences. In collectivist societies like India, family cohesion, religious beliefs, and community support often function as protective factors, buffering individuals against extreme psychological distress (Kirmayer et al., 2011). Shared caregiving, collective meaning-making, and spiritual coping may preserve a sense of agency and resilience even under chronic adversity. However, these protective factors do not negate stress entirely; rather, they interact with structural supports such as healthcare access, governmental response, and NGO interventions to shape overall stress outcomes.

Empirical studies comparing affected and non-affected populations consistently report higher levels of physical, sleep, behavioural, and emotional stress indicators among exposed groups (Bromet et al., 2011; Norris et al., 2002). Findings related to personal indicators, however, are more nuanced. Some research suggests that despite high stress levels, individuals may retain a sense of personal control or acceptance, often grounded in religious or cultural worldviews that provide meaning to suffering (Park, 2010).

Drawing upon this body of literature, the present study examines stress profiles in radiation-affected and non-affected villages of Varanasi across five dimensions—physical, sleep, behavioural, emotional, and personal indicators. The comparative design allows for a nuanced understanding of how chronic environmental exposure interacts with daily life and psychosocial functioning. By identifying both areas of vulnerability and resilience, the study aims to inform targeted, culturally sensitive interventions addressing mental health needs in environmentally at-risk communities.

Objectives

- To compare stress levels between radiation-affected and non-affected groups.

- To analyze differences across the five sub-dimensions of stress: physical, sleep, behavioural, emotional, and personal indicators.

Hypotheses

- H01: There will be no significant difference between radiation-affected and non-affected groups on physical indicators of stress.

- H02: There will be no significant difference between radiation-affected and non-affected groups on sleep indicators of stress.

- H03: There will be no significant difference between radiation-affected and non-affected groups on behavioural indicators of stress.

- H04: There will be no significant difference between radiation-affected and non-affected groups on emotional indicators of stress.

- H05: There will be no significant difference between radiation-affected and non-affected groups on personal indicators of stress.

Methodology:

The study comprised a total sample of 60 participants, divided equally into two groups. The radiation-affected group consisted of 30 individuals living in Pure village, Varanasi, an area identified as being exposed to electromagnetic and earth radiation. The non-affected group included 30 individuals from Gangapur, Varanasi, a comparatively non-exposed area. To ensure comparability, both groups were matched on key demographic variables such as age, gender, and socio-economic background. Stress levels were assessed using the Stress Indicator Questionnaire, a standardized tool consisting of 73 items that measure stress across five dimensions: physical, sleep, behavioural, emotional, and personal indicators. Responses were recorded on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 5 to 1, with higher scores indicating greater levels of perceived stress.

Procedure:

Participants were contacted directly and briefed about the study. Informed consent was obtained. Questionnaires were administered individually. Ethical standards of confidentiality and voluntary participation were maintained.

Statistical Analysis:

A comparative cross-sectional research design was adopted. Means, standard deviations, and t-tests were used to analyze differences between groups across the five dimensions.

Results:

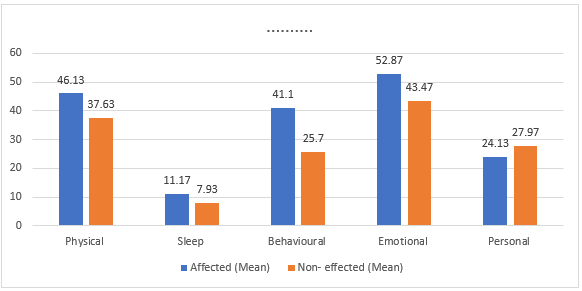

Physical Indicators: The affected group reported significantly higher scores (M = 46.13) compared to the non-affected group (M = 37.63), t = 2.80, p < 0.01.

Sleep Indicators: The affected group scored higher (M = 11.17) than the non-affected group (M = 7.97), t = 3.90, p < 0.001.

Behavioural Indicators: The affected group (M = 41.1) scored markedly higher than the non-affected group (M = 25.7), t = 6.19, p < 0.001.

- Emotional Indicators: The affected group (M = 52.87) reported higher levels than the non-affected group (M = 43.47), t = 2.93, p < 0.01.

- Personal Indicators: The difference between the affected (M = 24.13) and non-affected (M = 27.97) groups was not significant, t = -1.55, p = 0.06.

Discussion:

The findings indicate that stress levels are significantly higher in radiation-affected groups across physical, sleep, behavioural, and emotional domains. These results are consistent with prior studies of radiation and disaster-affected populations, which highlight the pervasive psychological consequences of environmental hazards (Bromet et al., 2011).

Physical and sleep indicators suggest that chronic radiation exposure not only affects health but also disrupts rest and recovery. Behavioural and emotional indicators confirm that stress manifests in heightened irritability, aggression, and emotional instability. Interestingly, personal indicators did not differ significantly between groups, suggesting that, despite environmental adversity, individuals in affected areas may maintain a subjective sense of personal control, possibly due to cultural resilience or government/NGO interventions.

The results underscore the need for comprehensive interventions in radiation-affected communities. Beyond medical aid, stress management programs, counselling services, and community mental health initiatives should be prioritized.

Conclusion:

The study concludes that radiation exposure is associated with significantly higher stress levels across most domains, except for personal indicators. This highlights the multifaceted impact of environmental hazards on mental health. Policymakers and practitioners should recognize stress as a critical health outcome in affected populations and design interventions that target both physical and psychological needs.

Acknowledgement: We are grateful to Mr. Rahul Kumar Maurya for his sincere efforts and dedication in data collection, which significantly contributed to the successful completion of this research.

References:

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. W. H. Freeman.

- Baum, A., Fleming, R., & Davidson, L. M. (1983). Natural disaster and technological catastrophe. Environment and Behavior, 15(3), 333–354.

- https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916583153004

- Bromet, E. J. (2012). Emotional consequences of nuclear power plant disasters. Health Physics, 103(2), 206–210. https://doi.org/10.1097/HP.0b013e31825f6533

- Bromet, E. J., Havenaar, J. M., & Guey, L. T. (2011). A 25-year retrospective review of the psychological consequences of the Chernobyl accident. Clinical Oncology, 23(4), 297–305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clon.2011.01.501

- Cohen, S., Kessler, R. C., & Gordon, L. U. (1995). Measuring stress: A guide for health and social scientists. Oxford University Press.

- Diener, E., Oishi, S., & Lucas, R. E. (2015). National accounts of subjective well-being. American Psychologist, 70(3), 234–242. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038899

- Edelstein, M. R. (2004). Contaminated communities: Coping with residential toxic exposure (2nd ed.). Westview Press.

- Eriksson, M., & Lundin, T. (2015). Stress, sleep disturbances, and health among survivors of the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness, 9(3), 258–264. https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2014.156

- Galea, S., Nandi, A., & Vlahov, D. (2005). The epidemiology of post-traumatic stress disorder after disasters. Epidemiologic Reviews, 27, 78–91.

- Havenaar, J. M., Rumyantzeva, G. M., Kasyanenko, A. P., Kaasjager, K., Westerman, R., Savelkoul, J., & van den Brink, W. (1997). Health effects of the Chernobyl disaster: Illness or illness behavior? A controlled study. Psychological Medicine, 27(3), 539–552. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291796004557

- Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer.

- McEwen, B. S. (1998). Stress, adaptation, and disease: Allostasis and allostatic load. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 840, 33–44.

- Morin, C. M., Rodrigue, S., & Ivers, H. (2006). Role of stress, arousal, and coping skills in primary insomnia. Psychosomatic Medicine, 65(2), 259–267.

- Murthy, R. S. (1990). Psychiatric aspects of the Bhopal gas disaster. British Journal of Psychiatry, 156(4), 551–553. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.156.4.551

- Neria, Y., Nandi, A., & Galea, S. (2008). Post-traumatic stress disorder following disasters: A systematic review. Psychological Medicine, 38(4), 467–480. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291707001353

- Norris, F. H., Friedman, M. J., Watson, P. J., Byrne, C. M., Diaz, E., & Kaniasty, K. (2002). 60,000 disaster victims speak: Part I. Psychiatry, 65(3), 207–239.

- Park, C. L. (2010). Making sense of the meaning of literature. Psychological Bulletin, 136(2), 257–301.

- Patel, V., Kirkwood, B. R., Pednekar, S., Weiss, H., & Mabey, D. (1998). Risk factors for common mental disorders in women. Archives of General Psychiatry, 55(6), 547–555.

- Raphael, B. (2000). Disaster mental health response handbook. Department of Human Services, Victoria.

- Selye, H. (1983). The stress concept: Past, present and future. In C. L. Cooper (Ed.), Stress research: Issues for the eighties (pp. 1–20). Wiley.

- Selye, H. (1956). The stress of life. McGraw-Hill.

- Shigemura, J., Tanigawa, T., Saito, I., & Nomura, S. (2012). Psychological distress in workers at the Fukushima nuclear power plants. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness, 6(2), 105–110.

- Tominaga, T., Hachiya, M., Tatsuzaki, H., & Akashi, M. (2014). The accident at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant in 2011. Health Physics, 106(2), 630–637. https://doi.org/10.1097/HP.0000000000000104

- Ursano, R. J., Fullerton, C. S., Weisaeth, L., & Raphael, B. (2007). Textbook of disaster psychiatry. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511544510

- World Health Organization. (2013). Health risk assessment from the nuclear accident after the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami. WHO Press.

- World Health Organization. (2016). Mental health and psychosocial considerations in radiological and nuclear emergencies. WHO Press. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/137035